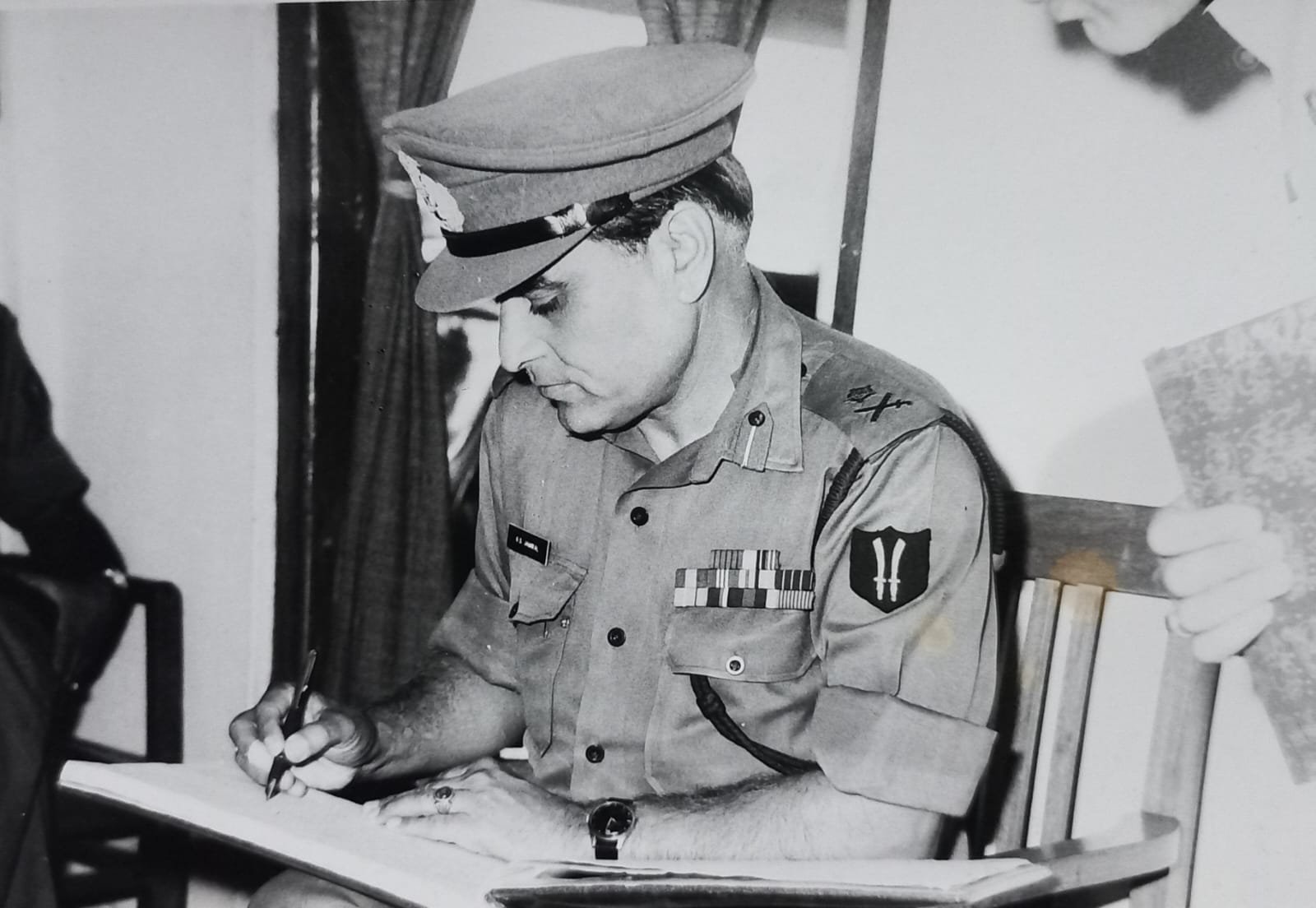

Reclaiming the Dogra Legacy: A Seminar on Identity and History By Maj Gen Goverdhan Singh Jamwal and Col J P Singh

In an endeavour to shed light on the rich history and identity of the Dogras, the ‘Voice of Dogras – London’ and the ‘History Department of Jammu University’ organized a remarkable three-day seminar from January 27 to 29, 2017. The seminar, titled ‘Regional Identities of Jammu & Kashmir with Special Reference to Dogra Identity,’ aimed to rectify the lack of recognition and distorted representations of the Dogra achievements.

The initiative was conceptualized by Ms. Manu Khajuria Singh, the founder of Voice of Dogras, and successfully implemented by the University. A total of 84 papers, all relevant to the subject, were presented during the seminar. Right from the inaugural session, it became evident that the Dogras possess a distinct history of conquest and empire building. However, this history has been overshadowed by a lack of documentation, as the Dogras themselves did not extensively record their achievements, and those who did, failed to give them their due credit.

During the seminar, it emerged that in the early 19th century, a unique empire was forged in Northwest India, comprising three diverse regions with no commonalities. The architects of this empire were Maharaja Gulab Singh and his great Generals Zorawar Singh, Mohd. Khan, and Mehta Baste Ram. The formation of a vast and cohesive empire without eroding regional and tribal identities was at the heart of the seminar’s discussions. Despite the unavailability of authentic records in the university library, the research scholars presented highly educative and enlightening papers on the subject.

One striking revelation was the transformation of the region’s communal harmony and unique identities over time. The divergence began with the end of Dogra Rule and reached its peak in the late 20th century when Kashmiri Pandits were forcibly driven out of the valley by their fellow Kashmiri Muslims, who had long celebrated their Kashmiriyat. This exodus was not limited to the Pandits alone; many Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians also migrated to the safety of the Dogra heartland. A comparison of present-day Bathandi with photographs from the 1990s provides undeniable evidence of this migration. While Pandits settled in places like Nagrota, Muthi, Mishriwala, Purkhoo, and Battal Ballian in Udhampur, Muslims established settlements in and around Bathandi. The inclination towards Jammu as a safe haven can be attributed to the compassionate and supportive nature of the former rulers and warriors. Even Punjabis who sought refuge during the peak of militancy in Jammu chose not to leave. It is worth noting that while Northwest India had been conquered by various empires such as the Mongols, Changiz Khan, Timur, Mughals, and Afghans, migrants did not flock to the lands of these conquerors. This highlights the unique Dogra identity, now referred to as Dogriyat, that attracted those seeking security and protection.

The foundation of Dogriyat was laid by the founding ruler and strictly followed by his descendants for over a century. The Dogra rulers did not impose their religion, culture, or language on the conquered areas. Remarkably, they refrained from establishing Dogra rulers, administrators, or lords over these regions, allowing them to govern themselves. This approach instilled confidence in their subjects, and it was this confidence that compelled minorities to migrate to Jammu whenever they felt threatened. Built over a century, this trust and sense of security led them to rush to the land of the Dogras without hesitation, where they were warmly welcomed. Even Muslims who felt unsafe in the valley sought refuge in Jammu. Unfortunately, the absence of extensive historical accounts by the Dogras themselves has led to an insufficient recognition of Dogriyat. It is often said that those who create history do not have the time to write it, contributing to the distortions in the history of Jammu and Kashmir. The scholars who presented their papers sincerely attempted to justify their knowledge, but the lack of access to authentic official records hindered their efforts. Nevertheless, credit must be given to Jammu University for providing a platform for these deliberations.

To understand why Dogra history has not been adequately represented or has been distorted, it is necessary to examine Sikh history. Many books written on the Lahore Darbar of Maharaja Ranjit Singh portray Gulab Singh as a vassal of the Sikh Empire, glorifying him and his generals for capturing Ladakh, Gilgit, Baltistan, and a significant part of Tibet. However, when the downfall of the Sikh Empire is discussed, Maharaja Gulab Singh and his family are denigrated, resulting in a noteworthy distortion. Consequently, contemporary historians have not given due credit to those who, through their valor, created a unique state in the early 19th century. The seminar emphasized the Dogras’ contribution in the conquest of Ladakh and beyond. The Dogras of the plains formed a formidable military force and achieved a military feat in the conquest of Ladakh that was unheard of in Indian history. General Zorawar Singh became the first Indian general to venture across the Himalayas four times. Moreover, Gulab Singh and Zorawar Singh did not stop at Ladakh; they continued northwards, extending the frontiers of the Jammu Raj to the point where three empires—Afghanistan, China, and Russia—once met.

Controlling, managing, and ruling this diverse State has always been a great challenge due to its geographical, climatic, linguistic, and cultural variations. Despite the lack of commonalities among the three regions, the Dogras remarkably governed the state for a hundred years. Their efforts came at a significant cost, as demonstrated by events like the tragic decimation of the entire Dogra force of 1200 at the hands of Baltis at ‘Bhoop Singh Ki Padi’ near Bunji in Gilgit. Only one Gorkha woman survived by jumping into the Indus River to recount the tale of tragedy. Various ballads, poems, folksongs, and stories, including those about General Baj Singh who laid down his life at Chitral during Maharaja Pratap Singh’s rule near the Sino-Soviet border, stand as testaments to the sacrifices made by the Dogras.

Another important outcome of the seminar was the recognition of the need to identify and rectify historical distortions. A comprehensive review of historiography is necessary to understand who and why the rich Dogra identity has been brushed aside in the political discourse of the state. The biased treatment towards the Dogras, the state forces, and Maharaja Hari Singh, in particular, has contributed to the distortion of Dogra identity. Therefore, it is crucial for historiographers to rewrite the extensive history of the Dogra rule, which dates back to June 17, 1822, when Maharaja Gulab Singh was anointed Raja of Jammu at Akhnoor.

Unfortunately, the State Forces faced great humiliation despite their defense of the state until its final accession and their subsequent role as part of the Indian Army. In an unfortunate turn of events, the regiment was ordered to be disbanded. However, a miraculous victory by the 4th Jammu and Kashmir Infantry, known as ‘Fathe Shibji’ and once a part of General Zorawar Singh’s force, changed the course of history. When attacked by a Pakistani brigade at Hussainiwala in Ferozpur in 1956, the battalion decimated the entire brigade, showcasing the battle-craft of the state force. This victory opened the eyes of the nation, leading to the integration of the entire state force into the Indian Army as a reward for their valor and sacrifices spanning centuries.

It is essential to bring these facts to light and provide a clear account of history. It is not too late to rectify the past. The historians, particularly the scholars from Jammu and Central Universities, need to acknowledge these aspects and take action. It is gratifying to note that Prof. R D Sharma, the Vice-Chancellor of Jammu University, who presided over the seminar, has committed to implementing the seminar’s recommendations. These recommendations include the necessity to reidentify history and culture with reference to Dogra identity, engaging the teaching and research faculty with prominent Dogras and their pluralistic culture, and fully integrating Dogra history into the academic curriculum at various levels of education.

The seminar on Dogra identity and history provided a significant platform for scholars and researchers to explore and discuss the subject in detail. By acknowledging and rectifying the historical distortions, fostering a sense of pride in Dogriyat, and incorporating Dogra history into academic discourse, we can honor the legacy of the Dogras and ensure their rightful place in history. The time is ripe for a comprehensive re-evaluation of history, and it is our hope that the scholars and historians of Jammu and Central Universities will rise to the occasion and bring forth a true and accurate representation of the Dogra legacy.