The Day to Forget: 13 Jul 1931

On 13th July 1931, a significant event took place that left a lasting impact on the State of Jammu and Kashmir. This event, orchestrated by the British and their agent Abdul Qadar, created a deep division in the heart of the State, leading to the formation of Jammu and Kashmir as separate entities. It marked the beginning of a wave of animosity that would plague the region for years to come.

Abdul Qadar, like a seed planted in the ground, sowed the seeds of hatred in the State. These seeds were later cultivated by Sheikh Abdullah, who turned them into a holiday against the Dogras, referring to the Maharaja and the J&K State Forces. Even the Dogras themselves succumbed to this sentiment, which I witnessed personally when they joined the Kashmiris in denigrating their own heritage. As a Member of the Legislative Council, I advised the Farooq Government in 1997 to abolish this holiday and focus on building bridges, but my advice fell on deaf ears.

The disintegration of the State that we, the Dogras, had built is a tragic outcome. The responsibility for this can be attributed to the Kashmiris themselves and, to some extent, us, the Dogras of Jammu, who aligned with the National Conference but failed to bridge the divide. I need not elaborate on the reasons behind this failure, as they are well-known.

I recall a conversation I had with Sardar Harbans Singh, a former minister, who relayed a message from Dr. Farooq Abdullah. Dr. Farooq stated that if I, General Goverdhan Jamwal, did not join the National Conference, he would not participate in the Assembly Elections, as he had abstained from the Parliamentary Elections. He also expressed a sentiment that resonated deeply within me: “If General Zorawar Singh could create this State, how could I not join to defend it?” It was a powerful sentiment that I found difficult to resist.

In 1993, when I conveyed to President Shri Shankar Dayal Sharma that Jammu was in a state of collapse, he was taken aback. He was unaware of the conditions prevailing in Jammu—the deteriorating industries, declining tourism, and the economic hardships faced by the people. He promised to address the issue with the Governor.

During our conversation, President Sharma made two observations that have remained etched in my memory. Firstly, he emphasized that the world acknowledges that J&K was created by the Dogras alone and that the Dogras defended the State and acceded it to India under the leadership of Maharaja Hari Singh. He questioned how we could let it go and how India could allow Jammu to suffer.

Today, as we reflect on the events of 13th July 1931, we are reminded of the deep divisions that were sown and the consequences that followed. Jammu, once the ladder that connected us to Kashmir, is now in a state of disrepair. Its economic foundations are crumbling, and its youth are forced to migrate in search of better opportunities. It is a dire situation that demands urgent attention.

As we move forward, it is crucial that we remember our shared history and work towards healing the wounds that divide us. Building bridges and fostering unity should be our priority. The day to forget, 13th July 1931, serves as a stark reminder of the need to rise above our differences and strive for a united and prosperous Jammu and Kashmir.

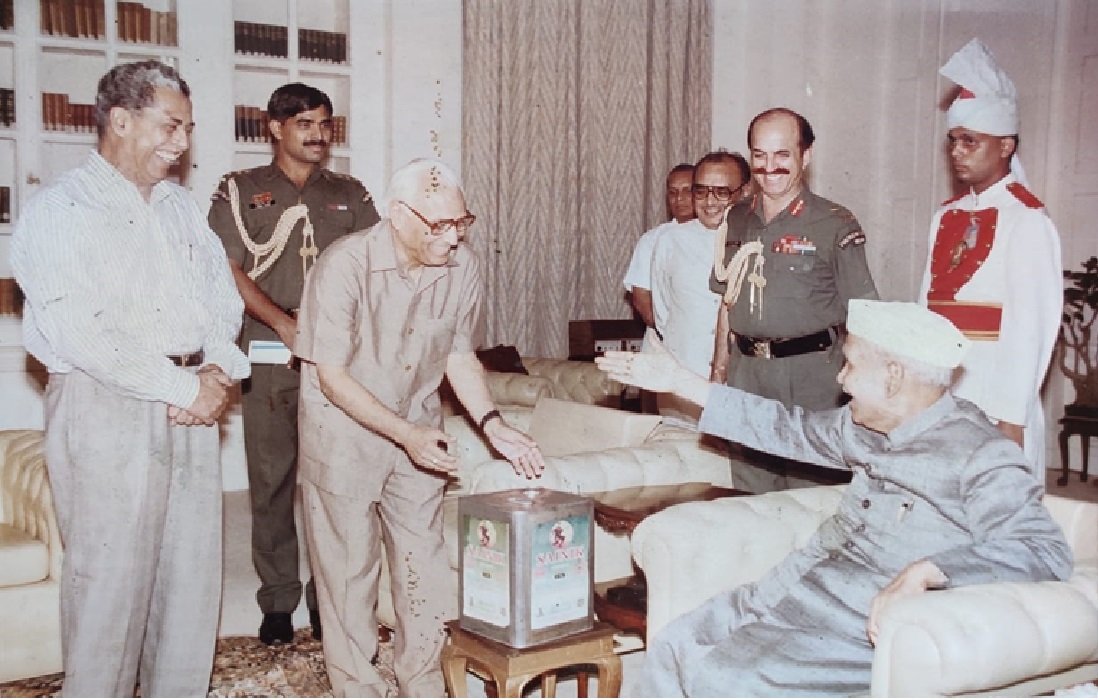

When I presented President Sharma with a tin of Sainik Vanaspati manufactured by the J&K Ex-Servicemen Cooperative Factory in Bari Brahmana Industrial Estate, he was immensely pleased with the initiative. General KV Krishna Rao, who had inaugurated the factory in the presence of Dr. Karan Singh and the then Chief Secretary, Shri Ghulam Rasool on 25th July 1993, shared the President’s enthusiasm. The factory was dedicated to the Veer Naries, the widows of soldiers, with 10% of the net profit reserved for their benefit. General Rao remarked, “I am so pleased, even surprised, that what I had advocated as Chief of Staff, to start such industries for the rehabilitation of the soldiers who retire very young—90% of them at the age of 33—has been realized by Gen Goverdhan Jamwal. He has set up a factory worth 7 Crores with a turnover of 100 Crores, providing 200 jobs directly and many more indirectly in my State alone.” However, I did not hesitate to share with the President the reality of the industry in Jammu. I explained that it was merely a façade, exploited by unscrupulous politicians and bureaucrats, with rampant corruption permeating the system. I expressed my lack of hope for the future, stating that Jammu’s industry was suffering.

How true I was. What I had told the President came true within seven years. The same factory, which had operated profitably for five years from its inception, was burdened with an illegal retrospective Ad Valorem toll tax of 4%. This unjust taxation crippled the unit, leading to its closure for the past twenty years. Although the High Court eventually revoked the government order after four years, it was too late, as the unit had already collapsed. It is important to note that this was a cooperative unit in which the State held 97% equity, but because it was located in Jammu and aimed to benefit the Ex-servicemen and their widows, it faced hurdles. To this day, the factory awaits government approval, despite possessing assets worth Rs 40 Crores. This unfortunate situation reflects the plight of industries in Jammu, underlining the challenges faced by the Dogras.

After the events of 5th August 2019, we had hoped for rehabilitation and progress, but our aspirations have been met with stagnation. The clock seems to be stuck, and the industry that could have provided livelihoods and opportunities for the people of Jammu remains in a state of neglect. The plight of the factory in Bari Brahmana serves as a stark reminder of the hurdles and systemic issues that hinder the growth and development of Jammu’s industry. It is imperative for the authorities to take proactive measures to revive the industrial sector in Jammu. Corruption and bureaucracy must be curtailed, and a conducive environment should be established to attract investments and promote entrepreneurship. By focusing on the potential of Jammu’s industry and addressing the challenges it faces, we can pave the way for a brighter future for the Dogras and the entire region.

The legacy of 13th July 1931 and its aftermath should serve as a catalyst for unity and progress. It is time to bridge the divisions that have plagued Jammu and Kashmir, foster economic growth, and provide opportunities for all its people. Only then can we truly honor the sacrifices of the Dogras and move towards a prosperous and inclusive Jammu and Kashmir.

The conversation with President Sharma took an important turn as he expressed concern about the industry in Jammu. He even assured me that he would personally speak to the Governor, but I know nothing happened. He then inquired about the state of tourism, and I provided him with a brief overview that still holds true today.

After the tragic displacement of Kashmiri Pandits from the Valley, there was a significant void, and the tourism industry in the State suffered greatly. General KV Krishna Rao, the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir at that time, called me and expressed his worry that tourists might forget about the State altogether, including the peaceful region of Jammu, which had much to offer. He suggested that I join the Jammu and Kashmir Tourism Development Corporation as a Director, alongside the Chief Secretary, Shri Ghulam Rasool.

During a subsequent meeting, I proposed that we take action to maintain a flow of tourists, particularly in Jammu, so that when conditions in the Valley improved, visitors would still consider coming to Jammu and Kashmir. I suggested identifying ten destinations in Jammu, including Poonch, Rajouri, Bhadarwah, Kishtwar, Patnitop, Sanasar, Basohli, and others. At each destination, we would set up around a hundred large family type tents to accommodate a thousand families at a time, making it even free of charge. This plan would attract approximately 5,000 tourists to the Jammu region throughout the year. Additionally, I proposed placing two shikaras (traditional Kashmiri boats) in Mansar Lake, two shikaras in Sruinsar Lake, and a small houseboat in Salal Lake. This would divert 10% of the Vaishno Devi pilgrims to these destinations and to places like Patnitop. The proposal was well-received, but unfortunately, nothing came of it for a year.

When I inquired about the progress from the Chief Secretary, he informed me that the Kashmiris had lost everything, and if the shikaras and houseboats were to go out of the valley, they would feel like they were losing their culture. This signalled the end of the plan. It seemed that the Kashmiris did not want tourists to come to Jammu, and this has been the reality for the past 31 years. I had conveyed this to the President during our discussion, explaining that it had indeed occurred.

The President assured me that he would discuss the matter with the Governor, but despite these discussions, no significant actions were taken. Consequently, Jammu continues to suffer due to animosities and a lack of regard for the region. This day serves as a reminder of why Kashmiris will never coexist harmoniously with us. It reinforces the notion that it would be better to part ways and establish two separate entities, living as brothers who support and assist each other.

The challenges faced by the tourism industry in Jammu and Kashmir highlight the need for concerted efforts to promote tourism in Jammu and rebuild the region’s economy. By focusing on the unique attractions and offerings of Jammu, and addressing the underlying issues that hinder tourism development, we can create a vibrant and prosperous future for the region. It is essential to foster a spirit of inclusivity, cooperation, and understanding between the people of Jammu and Kashmir, enabling both regions to thrive independently while maintaining a bond of brotherhood. It is hoped that Abrogation will continue otherwise the State will become worse that what it was at the time of the partition.