General Jamwal

When I learned of my selection to be the ADC of Yuvaraj Karan Singh Ji, the Sader-i-Riyasat of Jammu & Kashmir State, I was elated. This joy stemmed from my connection as an alumnus of the Shri Pratap Memorial Rajput Military School, established by Maharaja Hari Singh in memory of his uncle, Maharaja Pratap Singh Ji. This institution, founded with the aim of preparing young boys for the military service of Jammu & Kashmir, held special significance, especially considering the state’s status as the largest in all 565 princely states and the largest in India, established by the ancestors of Maharaja Hari Singh—Maharaja Gulab Singh and General Zorawar Singh. The Dogra Army, known as the J&K State Forces, played a pivotal role, given the strategic location of the state, surrounded by powerful countries like Russia, China, Tibet, Afghanistan, and Nepal, with Pakistan in close proximity. The Dogras, who founded the state in 1846, made significant contributions.

The historical journey, from Raja Gulab Singh receiving the title of Raja from Maharaja Ranjit Singh to the Grey TV event, marked by the anointing ceremony at Jio Pota Ghat of River Chenab, is a compelling saga. Raja Jaswant Singh Gulab Singh’s rise to Raja from an uneducated background in the Tehsil Samba village near Parmandal adds another layer to this narrative. Expressing a wish for his village to be transformed into a monumental tourist destination with a comprehensive history of the Dogras, I acknowledge the obscurity Dogras face due to their reluctance to self-promote through writing or reading about themselves. Thus, this narrative serves as a call to inspire young Dogras to explore their rich history, akin to my own fascination.

The compelling story continues with the heroic actions of General Zorawar Singh and later Brigadier Rajendra Singh in thwarting the British-engineered invasion of J&K State in 1947. The invasion involved 20,000 Ex-servicemen of Pakistan targeting our border areas, including Poonch State, now Poonch district of J&K, encompassing Mirpur, Bhimber, Kotli, Muzaffarabad, and the entire border region. It’s crucial to recognize the sacrifices made by the Dogras, who are our ancestors. The reminder of our lineage as descendants of Porus, the conqueror who defeated Alexander, serves as a testament to the historical significance often overshadowed by the narratives of the time.

The grandeur of Alexander, declared as the Great and the greatest Emperor by the Europeans, faced a silent challenger in the form of Dogras. The unacknowledged victory against the Greeks, with evidence suggesting Alexander’s demise on the banks of Chenab in Reasi, as depicted in the book “Dogras killed Alexander,” adds a layer of historical richness. These stories, often passed down through grandmother’s tales, underscore the need for a deeper understanding of our roots. The intricacies of these historical events lay the foundation for a narrative that aims to educate and inspire. The hope is that the retelling of these stories will kindle a renewed interest among the youth to delve into their history and appreciate the remarkable journey of the Dogras.

These historical revelations, often confined to the realm of oral tradition, underscore the incredible contributions of the Dogras. The unacknowledged victory over Alexander and subsequent European invasions of India showcases the resilience and military prowess of the Dogras. The validation of Alexander’s demise on the banks of Chenab in Reasi, near the Salal Dam, adds a layer of authenticity to these long-held tales.

The significance of this location, referred to in Persian or Greek, holds the key to unravelling a pivotal chapter in history. The book “Dogras killed Alexander,” authored by Dogra, Mangal Das Pangotra, serves as a beacon for those seeking a deeper understanding of these events, shedding light on a narrative often obscured by time and political interests.

Transitioning from historical revelations to personal experiences, my journey as a Dogra officer unfolded during a tumultuous period in the history of Jammu & Kashmir. Commissioned by Maharaja Hari Singh during India’s independence from 15th August to 26th October, I found myself in the midst of the British-engineered invasion of J&K State on 26th October. The war in Srinagar unfolded before my eyes, with the stark reality of death and wounded soldiers laying bare the gravity of the situation.

Witnessing the valour of Brigadier Rajinder Singh, who bravely went into battle but never returned, marked a somber chapter in my military service. The arrival of Indian Army aircraft, flying in to land at the Srinagar Airport, signaled a turning point. Assigned the duty of defending Badami Bagh Cantonment officers deployed along the river for three bitterly cold winter nights, we faced the severity of the situation with weapons at the ready, yet unused.

Reflecting on these challenging times, my commitment to knowing more about our ancestors deepened. The years that followed were marked by continuous exploration and learning, a dedication that would shape my understanding of the historical, political, and cultural dimensions of the region.

Joining Yuvaraj Karan Singh as ADC felt like a celestial intervention—a young Dogra officer, emerging from a village devoid of basic amenities, now serving the Sadar-i-Riyasat. My one-year training as an Army officer in Srinagar, Udhampur, and the hills of Patnitop under an adept instructor prepared me for the responsibilities that lay ahead. The journey from Lieutenant to captain, captain to Major, and the successful completion of crucial courses, including all Arms basic Engineers in Pune, Maharashtra, Weapons and the Junior Commanders Course at famous Infantry School Mhow, positioned me as a well-prepared and reasonably well-read Army officer.

As my narrative unfolds, the personal and historical threads intertwine, providing a comprehensive perspective on the challenges and triumphs of the Dogras and the evolving landscape of Jammu & Kashmir.

Having successfully completed various courses and examinations, I considered myself a fairly well-read Army officer, yet uncertain about the specific role that awaited me—whether it was to be a staff officer or the ADC to the Sadar-i-Riyasat. The Sadar-i-Riyasat, Yuvaraj Karan Singh, impressed me not just as a prince but as one of the most esteemed individuals in India. I later witnessed his intellectual depth during an 8-hour discussion on the Geeta with Radha Krishnan, the Vice President of India. My academic background, including a BA and studies in Sanskrit and history, seemed to be part of a divine plan, preparing me to serve the head of the state, a prince known as Yuvaraj and later the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir.

At that time, Maharaja Hari Singh had abdicated and been exiled, and Yuvaraj Karan Singh, still referred to as Maharaja, was at the helm of the J&K State Forces designated as Commander in Chief of J&K State Forces till integrated with Indian Army. He was later recognized with the Padma Bhushan, India’s second-highest civilian Award. My role as ADC, a position entrusted to assist the ruler, demanded that I acquitted myself well. The troubled state of Jammu and Kashmir, which had recently seen the dismissal of Sheikh Abdullah and the appointment of Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad as the Prime Minister, presented a challenging landscape. The state was engaged in a prolonged conflict with Pakistan, its neighbor, for 75 years, marked by four major wars, militancy, and terrorism.

The historical backdrop of the state’s transformation from a peaceful abode to a troubled region under attack needed thorough exploration. The British-engineered invasion through Pakistan, camouflaged as Raiders, unfolded as a planned and organized move. The involvement of British Chiefs in Pakistan and India, including Supreme Commander Auchinleck and Lord Mountbatten volunteering to remain Governor General of India, indicated a complex geopolitical landscape.

As I assumed my duties, I aimed to relieve the Sadar-i-Riyasat of staff-related challenges, allowing him to focus on the intricate affairs of Jammu and Kashmir. The state’s tumultuous journey, marred by conflicts and political transitions, warranted a deeper understanding—one that exposed the underlying reasons for the British-led invasion through Pakistan. The exploration of this historical narrative was essential to unravel the complexities that turned the once serene state into a hotspot of conflict, echoing the need for a comprehensive examination that delves into the untold chapters of Jammu and Kashmir’s history.

The intricacies of Jammu and Kashmir’s historical narrative reveal a calculated move by the British, employing a strategy to ensure the transfer of J&K state to Pakistan. Lord Mountbatten’s role in volunteering to remain Governor General of India, alongside Supreme Commander Auchinleck, was not merely coincidental. It was a well-thought-out plan to exert pressure on Maharaja Hari Singh, coercing him to accede to Pakistan. The subsequent invasion orchestrated by Pakistan, while Mountbatten stayed in, created a web of manipulation involving Jawaharlal Nehru and Maharaja Hari Singh.

This carefully constructed narrative, driven by political manoeuvring and imperial interests, forms the crux of the story I unravel in my book, “Valour and Betrayal.” The book delves into the depths of my knowledge, acquired over the years, to present a comprehensive account of the events that unfolded during that critical period. Through meticulous research and a dedication to uncover the truth, I aim to shed light on the valiant efforts of those who defended Jammu and Kashmir against external forces and the betrayal that unfolded behind the scenes.

The story encapsulates the struggle of a state that, once known for its tranquillity, found itself at the centre of geopolitical turmoil. The persistent conflicts, spanning major wars, militancy, and terrorism, are rooted in the political machinations of the past. By recounting these historical events, I aim to contribute to a broader understanding of Jammu and Kashmir’s complex journey, ensuring that the sacrifices and struggles of those who defended the state are acknowledged and remembered.

“Valour and Betrayal” serves as a testament to the resilience and bravery of the people of Jammu and Kashmir, highlighting their untold stories and the challenges they faced in the face of external interference. The book stands as a tribute to the dogged determination of those who fought against the odds, and it endeavours to fill the gaps in the historical narrative, ensuring that the true legacy of Jammu and Kashmir is preserved for generations to come.

As I’ve elucidated previously, it appears that God had a preordained plan for my life. At the age of 25, despite having received a rather modest education in non-prominent schools, I found myself in a position where I was diligently preparing for a significant role. This role was to serve as the Staff Officer or ADC to Yuvaraj Karan Singh, undertaking the responsibilities of a military secretary, to the head of the state – the largest and most intricate state in India.

This state, Jammu and Kashmir, had been partitioned, leaving behind what we referred to as Azad Kashmir with Pakistan and what we labelled as Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir. These geopolitical changes had significantly altered the landscape of J&K State. Despite its mutilated state, certain portions were now under Chinese control. At that time, Karan Singh, who also held the position of Commander-in-Chief of the J&K state forces, was at the helm. It was this regiment, my force, which eventually transformed into a regiment in the Indian Army, a development I will elaborate on later.

This appointment as ADC was exceptionally sensitive due to the geopolitical intricacies and the duties it entailed. As an ADC, the responsibilities were to ensure the comfort, security, and well-being of the person I was working with – in this case, the esteemed head of the state. For us, he was not only the revered son of the most esteemed ruler but also a symbol of the Jamal Dynasty, to which I belonged, albeit at the lower rung. The job held profound significance for me, and I took it seriously, even though I may not have fully grasped its depth and complexity at the time. Later in life, after retirement and assuming the role of President of the Dharmarth Trust, overseeing over a hundred shrines, including prominent ones like the Raghunathji Temple, Ranveerashwar Temple, Shankaracharya, Kheer Bhavani, Haridwar, and Varanasi (topics I will delve into later), I reflected on how it seemed that God had meticulously prepared me for this specific role.

This narrative is not just a personal account but also a testament for posterity. It aims to shed light on the gravity of such roles for the community, the people of Jammu, the Dogras, and the young officers of the Army who are often entrusted with the significant assignments of serving as ADCs to the Governors of the country.

In those times, the landscape of Jammu and Kashmir was distinctly different from other regions in various aspects. With a Muslim population comprising 70%, the region had faced significant territorial losses to Pakistan, leaving it with less area but still a one-third population. Undeterred by these challenges, I committed myself to giving my best, determined to learn from this unique and demanding role.

Serving as the ADC to the erudite Prince of India, Dr Karan Singh, was an invaluable experience. Before delving into the specifics of the duties and accomplishments during my tenure, I recall a conversation with Maharaj Saab after my retirement. I expressed to him that I felt chosen by a higher force for this position. While many prestigious institutions existed in India and abroad for higher studies, such as Oxford and Harward University. I shared with Maharaj Saab that my three years of service as ADC was like a comprehensive course in perfect staff duties. The subject matter involved working closely with the head of the state, a Prince from the largest and strategically vital former princely state.

Reflecting on my service, I realized that I had acquired insights and experiences equivalent to a three-year course, particularly delving into the intricacies of staff duties with a royal figure in the midst of challenges like the Kashmir dispute. Jammu and Kashmir, the largest princely state, retained strategic importance, and it was still grappling with issues like the Kashmir imbroglio and many issues which make the state most troubled in the world still dragged in the UN, three Countries Armies deployed face to face.

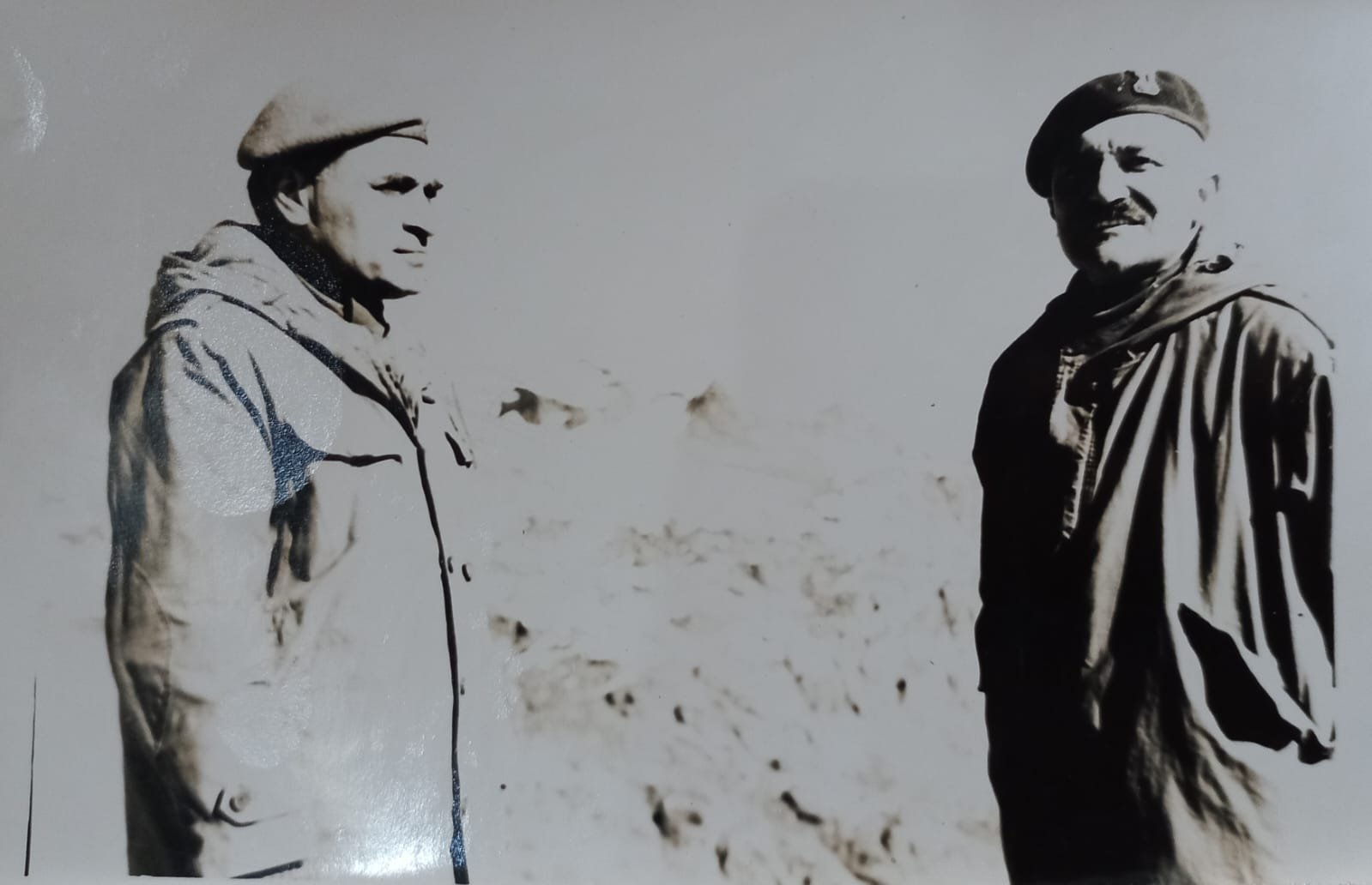

My journey began on a significant note, with my first day of service coinciding with the Jammu and Kashmir War at Uri. It was at Uri, precisely where Brigadier Rajinder Singh had blown the bridge. This strategic act prevented Jammu and Kashmir from becoming a part of Pakistan. Stationed at Uri Bridge, my initial experiences involved training under war conditions with the elite battalion of Kumaunis, the 4th Battalion of the Kumaon Regiment. This distinguished battalion, commanded by generals such as Thimayya and Sheernagesh, played a crucial role in shaping my understanding of military operations.

Before joining my assigned battalion, the 9th Jammu and Kashmir Rifles (Rudarshibnab), which had a historical lineage serving in Gilgit Baltistan during World War II, I had undergone training in war conditions. The battalion, raised in 1940 by Colonel Dhanantar Singh Jamwal from the village of Agore in Jammu district, held a significant place in the region’s military history, being situated near the banks of the Chenab River in Akhnoor.

This marked the beginning of my journey in an area laden with historical significance and complexities, setting the stage for the multifaceted experiences that would shape my understanding of duty, service, and the unique challenges that Jammu and Kashmir presented.

Col Sansar Singh’s leadership as the Commandant of the J&K Training Centre at Satwari had significantly contributed to the formation of a formidable unit, the Rudar Shiv Nabh battalion. This unit, recognized as one of the best in the Jammu and Kashmir state forces, had a rich history of service. It had served for three years in the North West frontier now in Pakistan under British command and later relocated to Srinagar, where it was designated as the reserve battalion of the Kashmir Brigade defending Kashmir.

However, the strategic movements of the battalion became a crucial chapter in its history, as described in my Autobiography and book “Valour and Betrayal.” General Scott’s decision to move the Battalion from Srinagar to Poonch in August 1947 had left Kashmir vulnerable, lacking reserves and troops in depth during the final attack. As part of the Rudar Shiv Nabh battalion, I witnessed and analysed these events, providing me with a unique perspective on the unfolding military dynamics.

Upon joining the area, I encountered the challenging situation of the J&K state forces. They were partly deployed in J&K but had been largely ousted from the region, awaiting disbandment. Three battalions that had played pivotal roles in the Kashmir War 5 J&K (which saved Jammu), 6 J&K (fought in Gilgit Baltistan), and 8 J&K (which saved Poonch) had already been disbanded in 1951. The remaining regiment was awaiting disbandment, considering the ongoing reduction in the Indian Army, which had already decreased from 25 lakhs to about 4 lakhs.

The Kashmir War had concluded, and the United Nations resolution called for a withdrawal of Pakistan forces from Jammu & Kashmir and also drastic reduction in the Indian Army. Only J&K State Forces were to stay, yet three battalions had been disbanded. Such was the hostile attitude of the Indian Govt and also of the Indian Army towards the Dogra Forces of the Maharaja. Not only by the Govt, Nehru, but even by the Indian Army. The State Forces were looked down as inferior forces who had allowed the J&K situation turn sour for the Indian Army. I have seen and faced the remarks for years almost till the Hussainiwala operation in 1956 and even thereafter till 1963 when integrated with the Indian Army but more till 1965 when the J&K Forces did well in war like 9 JAK Rifles in Khemkaran which saved Asaluttar and is remembered for creating Patton Nagar. Its full account is given in my book ‘Valour and Betrayal’.

In 1956, at Hussainiwala, the 4th Jammu and Kashmir Infantry, which had suffered considerably, became the focal point of another turning point. This incident, detailed in my book, played a role in altering the course of events and decisions related to the disbandment of certain units.

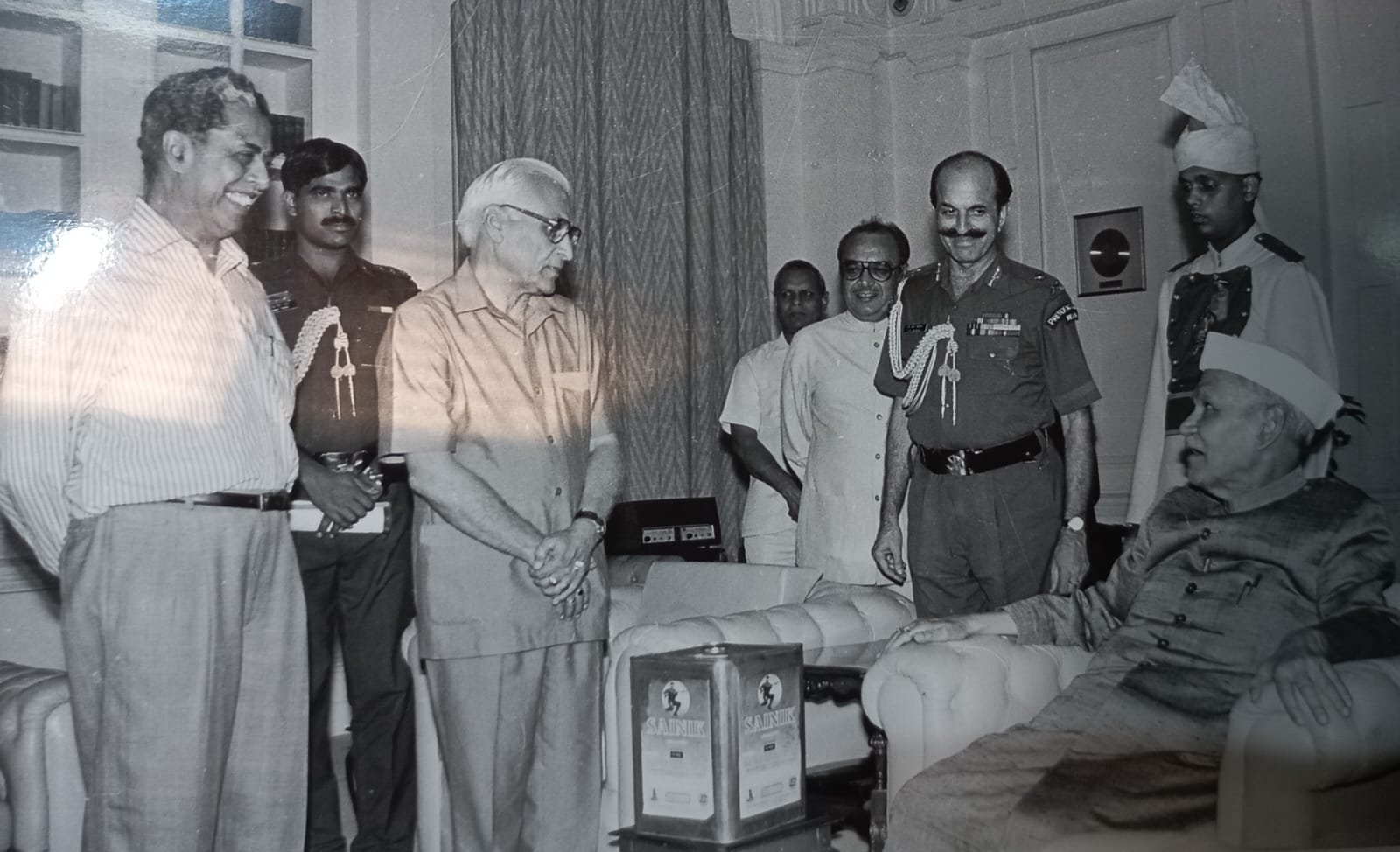

This complex and layered history provided the backdrop to the state of Jammu and Kashmir, with its young Sadar-i-Riyasat, Dr Karan Singh, at the helm. He had taken on the onerous duty at the age of 19, and by the time I joined him at 26, he was 23. The two and a half years’ difference in our ages highlighted the historical context and the weight of responsibilities we carried during those turbulent times.

Having served under Dr Karan Singh during those significant years, then Yuvraj Karan Singh, who was in the process of completing his graduation and subsequently preparing for his Doctorate when he was declared first class first by Delhi University in 1961 beating all records was a transformative experience. During this period, I viewed my role as akin to pursuing a course at the University of Life, and I approached it with utmost seriousness. I invested considerable effort into self-improvement, focusing on refining my language, enhancing my English proficiency, and honing my speaking, thinking, and behavioural skills. In fact, self-improvement learnt here and practiced I continued all my life till today at 96.

The environment I found myself in demanded a certain etiquette and comportment, especially when interacting with rulers, rajahs, princesses, generals, ministers, and thinkers. This was an aspect of my training that I had not received previously, but I recognized its importance and took it upon myself to equip myself with the necessary skills. The emphasis here is on the dedication I applied to this endeavour, tirelessly working to transform myself into a well-rounded and cultured individual. It stood me in good stead throughout my life in Rashtra Pati Bhawan or even after retirement.

My commitment extended beyond the regular working hours; it was a continuous, 24-hour effort. In the process, I even took on the task of writing my autobiography and a novel in Hindi titled “Gori,” which was eventually published in three Additions in 1963-64. The novel even made its way into a film, though the name escapes me at the moment. These creative outputs were unintended byproducts of my service with Maharaj Saab, Dr. Karan Singh.

Reflecting on those years, I realized the profound impact of the tumultuous period during which I served as ADC. Sheikh Abdullah had been imprisoned, Bakshi Gulam Mohammad had assumed the role of prime minister, and Yuvraj Karan Singh had fully matured into the Sadar-i-Riyasat. The interactions I witnessed, including Dr Radha Krishnan’s stay with Yuvraj Karan Singh in the palaces, his addresses in the assembly, and his visit to Banihal for the inauguration of the Jawahar Tunnel, were invaluable lessons in statesmanship and governance.

These experiences served as a unique training ground for the future, providing insights and skills that proved to be invaluable throughout my life. The three years spent in such a dynamic and historically significant period laid the foundation for my understanding of leadership, governance, and the intricacies of serving in roles of great responsibility.